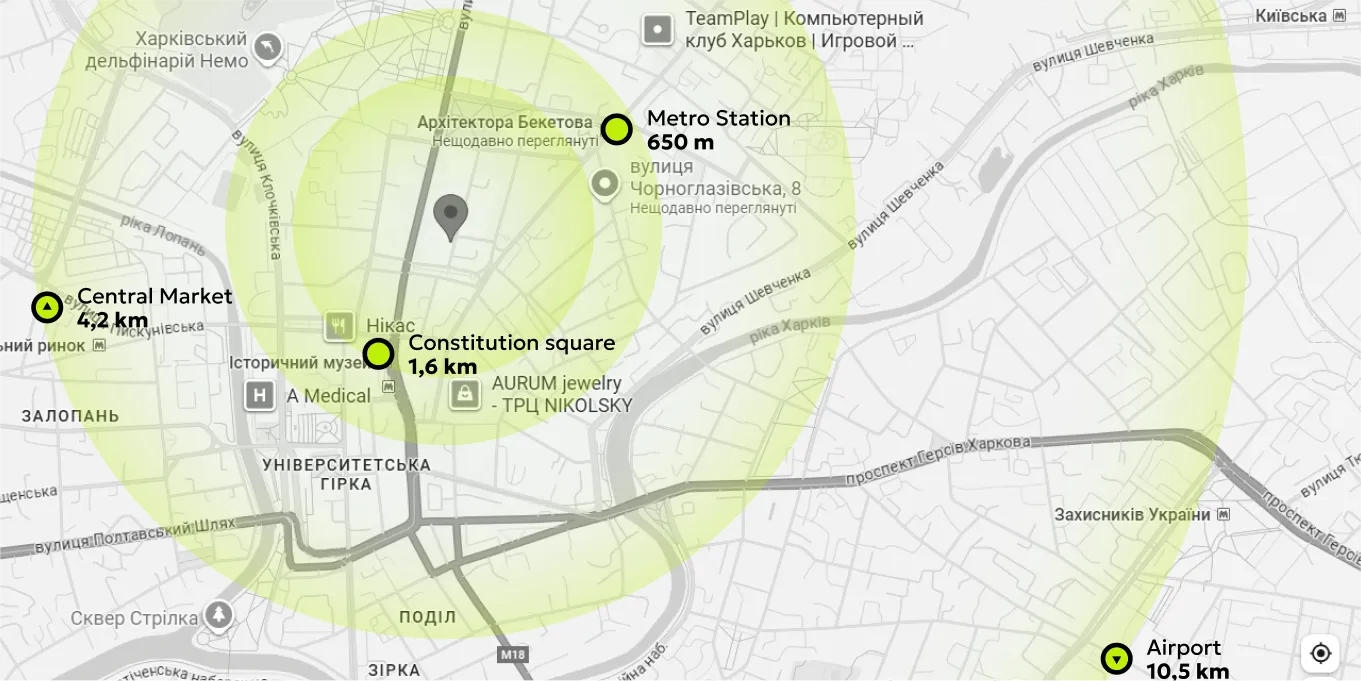

The building on Hoholia Street 3 in Kharkiv is now a ruin, waiting for a renovation. Still, it is an essential element of a historical location and a heritage of a unique ethnic community.

The small Hoholia street is one of the most significant for the city's architectural heritage — a row of historical buildings that embody Kharkiv's multicultural nature. It has changed its name at least five times, but the current name, after Ukrainian-Russian writer Mykola Hohol, has stayed since 1909.

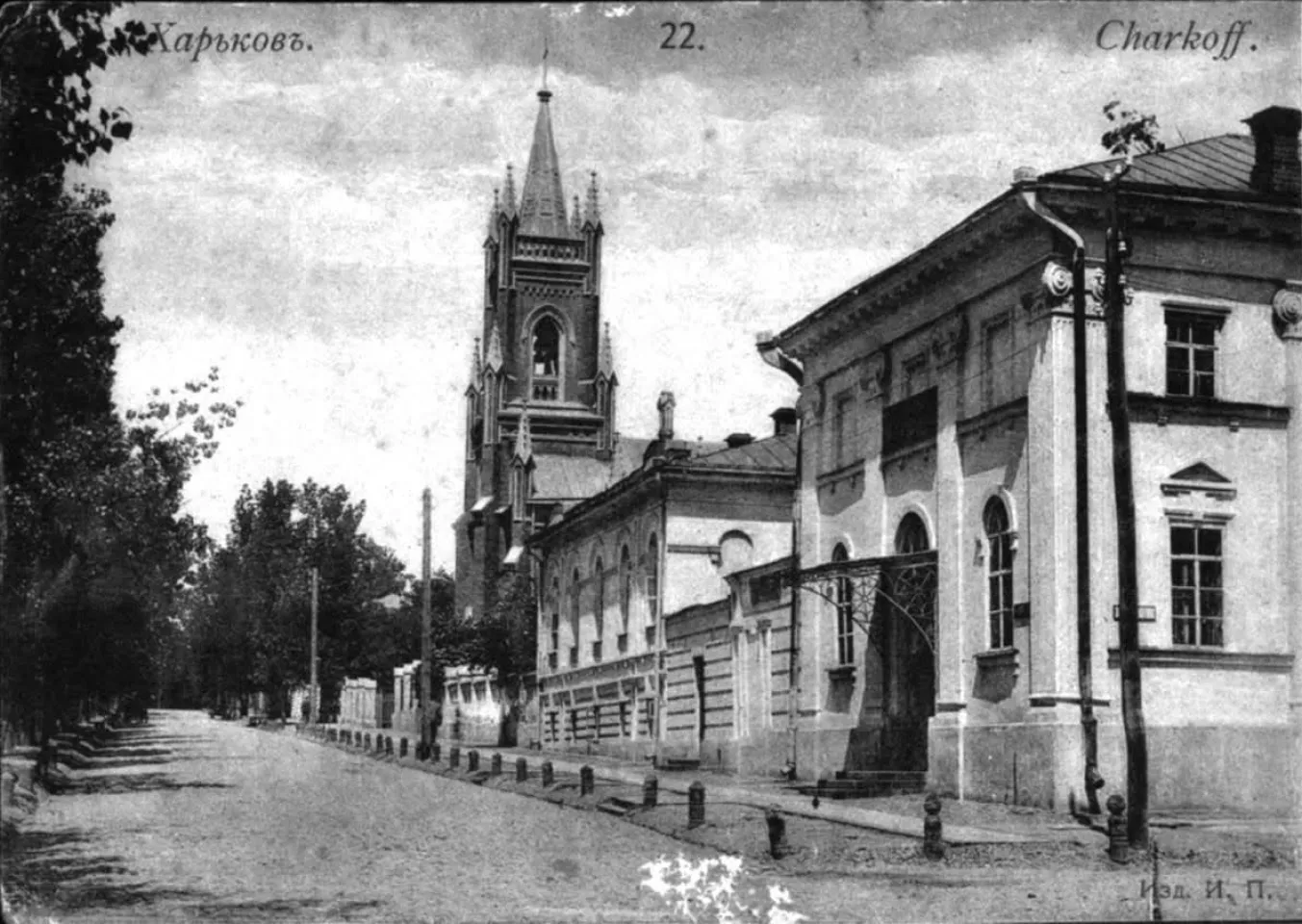

In the 18th century, there were barracks, stables, a gunpowder armory, and a prison. In the 19th century, German craftsmen started to occupy the street. The German commune had built a Lutheran Kirche, a preacher's house, and a school. Unfortunately, the Neo-Romanesque Kirche with a huge clock tower was destroyed in the mid-20th century during Soviet times.

Another local community was Catholics, which consisted predominantly of Poles. They built a Roman Catholic church. This neogothic building remains a main attraction of the street.

One end of Hoholia Street opens onto the park where the Orthodox Church of the Myrrhbearers was located. Originally built in 1783, the Baroque building was demolished in the 1930s. Ten years ago, a new church was built on that site.

One small street, 330 meters long, integrated four different religious denominations. The fourth was the Crimean Karaites. They are a Turkic-speaking ethnicity native to Crimea who practice Judaism. Karaite Judaism differs from Rabbinic Judaism. For instance, they recognise the Tanakh and Torah as holy books, but not the Talmud.

Researchers claim they are of ethnic Jewish origin, but many Karaites themselves tend to link their origin to the Khazars. After the annexation of Crimea by the Russian Empire in 1783, many Karaites were deprived of their land, left the peninsula, and some moved to Ukraine. The Russian Empire, which Ukraine was a part of, soon introduced antisemitic laws that allowed Jews to permanently settle only within specific borders, in the Western region, including Kharkiv. Karaites, therefore, tended to emphasize their difference from Jews. That distancing somewhat helped later in the 20th century during the Holocaust, since the Nazis formally granted a legal status to Karaites, separating them from persecuted Jews. Hundreds of Ukrainian Karaites were still massacred, though.

Karaites started to settle down in Kharkiv in the mid-19th century. They were mainly engaged in the tobacco business and built several cigarette factories. Some were engineers and doctors. According to a local historian, Oleksandr Dziuba, who also serves as a hazzan (a clergyman) in the kenesa (a Karaite synagogue), "the Karaites were one of the richest ethnic groups before the Russian revolution. The number of millionaires per capita was higher than among others."

The Kharkiv kenesa is still preserved and is currently the only operating kenesa in continental Ukraine.

In the 1900s, one of the local Karaites, a surgeon named Mangubi, bought a plot with a two-storey private clinic on Hoholia Street, which he extended with an annex. His new medical facility included a balneary. Dr. Mangubi specialised in urological and sexually transmitted diseases and surgery.

The same house hosted a Karaite charitable association. Dr. Mangubi was its chairman.

Also, some rooms were available for rent, as it follows from advertisements in newspapers of the time. Hot-water heating, electricity, meals, and a doorman are mentioned. One of the advertisements suggests a five-room apartment for rent.

House #3 is the oldest one on Hoholia Street, believed to have been built in the mid-19th century. It has recognisable elements of typical classicistic houses of the time, which one still finds in abundance in different places of the historical centre. The variations of such exteriors were represented in 'albums of facades' that used to be published in the early 19th century.

The facade is somewhat eclectic, but it strongly influences the Empire style, which includes rustication and fan-shaped keystones above the ground-floor windows and distinctive cornices decorating the windows of the upper floors.

By the left side of the house, there used to be an entrance to the courtyard for carriages. Two entrances were decorated with openwork metal canopies. Two balconies faced the street, according to archival photos.

Initially, it had two stories and a semi-basement. Later, the third floor was added to the building—differences in the brickwork reveal it. Then a perpendicular three-storey wing was added.

Mangubi completed the extension in 1912 with a three-storey brick annex in the modest Art Nouveau style. An architect, Mykola Kolodyazhny, designed that part. This new wing enclosed the plot, forming a patio.

During the last decades, the house has declined. In the early 2000s, there were attempts to build an addition on top of it, and that structure remained until now.

In 2017, a local architecture practice, O.S.A., presented a new reconstruction project for a GOGOL hotel. The facade was expected to be partially restored. However, the project was not approved.

Later, in 2021, the company Alter Development addressed the O.S.A. and asked to design a new reconstruction project in order to reestablish a classification of the building as a historical monument.

It suggests the three original buildings will be preserved to varying degrees and will become a multifunctional complex. The main facade will receive a contemporary interpretation—the same eclectic features with the elements of Empire style, but with some influence of an American architectural school.

The main building will have five floors, and its total height will not exceed that of a constructivist house on the right, as the fifth floor will be positioned farther away from the street. Thus, the building will not conflict with another neighbouring house, an Art Nouveau monument on its left.

The renovation project aims to harmonise the complex with the neighbouring buildings visually.

As a socially responsible business, Alter Development aims to preserve historical memory through projects such as this.