The historical Rosenfeld House in Kharkiv, abandoned and deteriorated for decades, has recently become a prominent example of sensible restoration.

n for its unique constructivist architecture, which started to bloom in the 1920s, after the city became the region's industrial and financial centre. However, the Art Nouveau style (or Jugendstil and Sezessionstil) is no less critical for its urban landscape. Both styles coexist harmoniously, resonate, intertwine, and frequently intercross on the timeline. Many local Art Nouveau buildings were so-called 'revenue houses' — rental tenements, known as 'immeubles de rapport' in France, 'inmuebles de alquiler' in Spain, etc. For wealthy owners, such property meant a stable and long-term source of income. Apartments in those buildings shared similar layouts, but façades looking onto a main street were usually splendidly decorated.

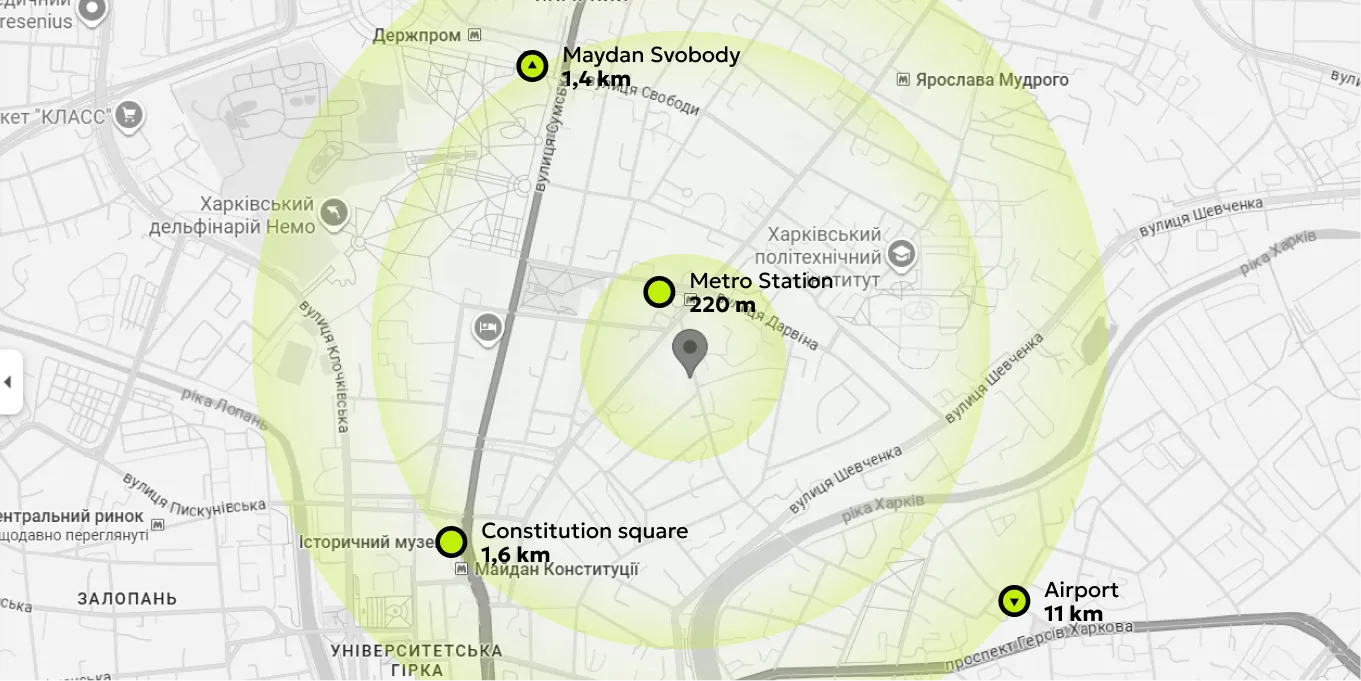

By the end of the 19th century, marginal areas to the North of the historical city centre were built up by private manors and homesteads with gardens. Eventually, they gave place to bigger multi-family revenue houses, including those on Chornohlazivska Street. The street was named after a noble family. Oleksandr Chernohlazov was awarded a high rank and property for his role in the Russo-Turkish War in the 18th century. His heirs owned some real estate on this street.

In 1912, a prosperous pharmacist, Lazar Rosenfeld, bought a lot there and ordered a builder, Mykola Kolodiazhniy, to develop projects of two residential buildings. They were finished the following year under the supervision of an engineer, Mykhailo Roitenberg. Nowadays, they have numbers #6 and #8.

The Rosenfeld House #8 is a five-story building, a typical example of late Kharkiv Modern Style, eclectically complemented by classicistic elements such as Empire-style festoons and pilasters that stretch throughout the four upper floors. The entrance is flanked by two sculptures of cherubs. On the top, on the decorative gable wall, are two mascarons depicting Hermes, a deity of trade and success. High pilasters and elongated windows invest the façade with a distinctive vertical rhythm.

Some sources claim that the construction turned out to be too expensive for Rosenfeld, so he had to sell both buildings. Nevertheless, after the sale, he quartered himself in one of the rented apartments. The project's engineer, Roitenberg, rented another apartment.

Both houses survived to our times. The #6 remained inhabited and had been renovated, although it had lost an extension and some original elements of the façade.

Meanwhile, the house #8 declined. In the 1980s, the residents were moved out of the wrecked building. Later, its roof and interior elements collapsed—one could see the sky through its windows just from the street. Basically, the building turned into a skeleton. The façade was still standing, though.

There were a few attempts to save the building, and at some point, the walls were reinforced from the inside with a metal framework. In 2013, the municipal government decided to deprive it of its conservation status and tear it down. Officials were afraid that the collapse of the building might damage the two neighbouring houses. Back then, the Rosenfeld House was owned by one of the Ukrainian banks that went bankrupt in 2015. Fortunately, dismantlement never happened. The building kept deteriorating, though, with a bright yellow alarm on its entrance door: a conceptual work by Kharkiv street artist Hamlet Zinkivskyi, a writing "Every window is a door".

In 2020, Alter Development started an ambitious reconstruction of the ruined building. As most of the internal structure had already been lost, the engineers designed a new one according to a new function: an office space. Some elements, such as authentic staircases, which were possible to preserve, remained. The new structure made it possible to readapt the internal layout to contemporary standards for office buildings.

The façade, on the other hand, has been fully restored, as close to the original as possible. Authentic bricks were reused, and Mettlach tiles and granite elements were preserved. The architects of the projects reconstructed the original window and door frames. A shade between light grey and neutral beige has been chosen as the primary colour of the façade. White plaster decorations and the entrance subtly stand out against this background. The sculptures, mascarones, and other plasterworks were reconstructed by a local Kharkiv sculptor, Oleksandr Ridnyi.

The architects added a functional attic floor. This intervention did not change the overall height of the building. In recent decades, the addition of superstructures to historical buildings has become pervasive in Ukraine. As is often the case, they violate not only the design of the original exterior but also distort the general proportions of the house. Yet, there are contrasting samples of delicate additions that make projects more commercially attractive and functional without ruining the original design. The Rosenfeld House case is one of them. Besides, an open-air recreation area will be arranged on the roof.

In general, restoration instead of demolition and new construction is a choice in favour of sustainability and responsible development. This should be even more so in the case of listed buildings.

Due to its proximity to the Russian border, Kharkiv is being severely hit by air strikes. The northern residential districts in the North of the city have suffered the most substantial damage, but dozens of historical buildings in the central areas have also been affected. This makes restoration and preservation projects of Kharkiv's distinctive and unique architecture crucial.